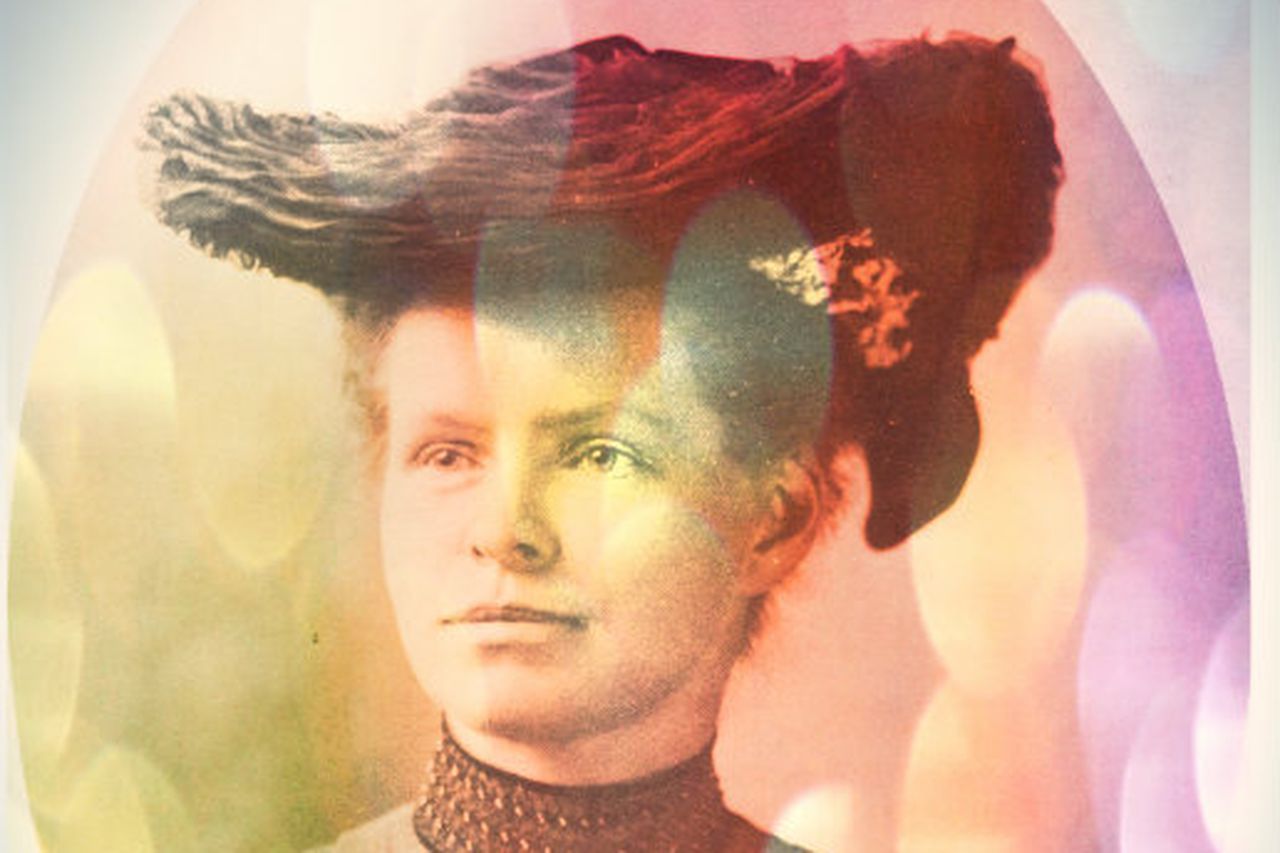

Nettie Stevens discovered XY sex chromosomes. She didn't get credit because she had two X’s.

At the turn of the 20th century, biologist Nettie Stevens was driven to solve a scientific mystery that had perplexed humanity for millennia. The mystery was so simple but daunting: Why do boys become boys and girls become girls? In her pioneering work at Bryn Mawr College, Stevens discovered the sex chromosomes that make the difference.

Today would be her 155th birthday. Google is celebrating her accomplishments today — she’s featured in the Google Doodle — and so should we.

Before Stevens, we were utterly clueless about how embryos become boys or girls

Thanks to Stevens’s work — and the work that built upon it — we now know that sex is hereditary, and that dads’ sperm in particular determine the sex of offspring.

But for most of human history, this question was an absolute mystery — and it yielded some interesting theories.

Aristotle believed a child’s sex was determined by the body temperature of the father during sex. “Aristotle counseled elderly men to conceive in the summer if they wished to have male heirs,” the textbook Developmental Biology explains.

In 19th-century Europe, it was widely believed that nutrition was the key to sex determinant. Poor nutrition led to males, good nutrition to females.

And throughout the centuries, other gonzo theories abounded.

The 18th-century French anatomist Michel Procope-Couteau (the author of The Art of Having Boys) believed that testicles and ovaries were either male or female.

Procope-Couteau “suggested the best way to control a child’s sex would be to remove the testes or ovary connected with the unwanted sex; though a less drastic mean for ladies would be to lie on the correct side, and let gravity do the rest,” according to The Evolution of Sex Determination, a book by biologists Leo W. Beukeboom and Nicolas Perrin.

All of that was nonsense, we’ve learned, thanks to Stevens.

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/6752625/Nettie_Stevens_microscope_(2).jpg) |

| Microscopes haven't changed much... |

The mealworms that held the secret of sex determination

Stevens was born in Vermont in 1861 and got her start in science at the relatively late age of 35, when she had saved up enough to enroll in a small startup university in California. It was Stanford, and she thrived there, earning both a bachelor’s and a master’s degree by 1900.

After Stanford, Stevens pursued a PhD — a level of education very rare for women of her time — at Bryn Mawr in Pennsylvania. It was there that she turned her attention to solving the problem of sex determinism.

In the early 1900s, the idea that chromosomes contained hereditary information was still a brash new theory. The works of Gregor Mendel himself were only rediscovered in 1900 (Mendel had no audience for his ideas while he was alive), and the scientific community was trying to work out the mechanisms of how traits — including sex determination — were passed between generations.

Stevens wanted to know how (and if) sex was passed on through genetic inheritance. She was making observations with a microscope of the chromosomes in Tenebrio molitor — the mealworm beetle — when she discovered something that had eluded humanity for millennia.

Stevens observed that the female mealworm’s cells had 20 large chromosomes. The male had 20 chromosomes as well, but the 20th was notably smaller than the other 19.

“This seems to be a clear case of sex determination,” Stevens wrote in, a report summarizing her findings.

She concluded (correctly) that this difference could be traced back to differences in the mealworm sperm. The sperm had either the small version of the 20th chromosome or the large one. “The spermatozoa which contain the small chromosome [determine] the male sex,” she wrote, “while those that contain 10 chromosomes of equal size determine the female sex.”

(She didn’t call these chromosomes X or Y. That naming convention would come later.)

Her sex chromosome discovery in 1905 “was the culmination of more than two thousand years of speculation and experiment on how an animal, plant, or human becomes male or female,” historian Stephen Brush explains in The History of Science Society. “At the same time it provided an important confirmation for the recently revived Mendelian genetics that was to become a central part of modern biology.”

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/6755087/Screen%20Shot%202016-07-07%20at%209.46.15%20AM.png) Studies in Spermatogenesis.

Studies in Spermatogenesis.Stevens didn’t get credit for her revelatory work — at first

Stevens’s colleague and mentor E.B. Wilson — a legendary biologist in his own right — is more commonly cited as the discoverer of sex chromosomes.

The reason is simple: sexism.

Wilson was working on the same questions as Stevens, and he published a similar result around the same time. Wilson had worked on a species where the male actually has one less chromosome than the female, which is less common in nature. Stevens’s model of an X and Y chromosome is the basis for human sex determination. Plus, Stevens’s model better supports Mendel’s theory on genetics — that some genes take on dominant roles and override the instructions of their gene pairs.

“It is generally stated that E. B. Wilson obtained the same results as Stevens, at the same time,” Brush writes. But “Wilson probably did not arrive at his conclusion on sex determination until after he had seen Stevens' results. ... Because of Wilson's more substantial contributions in other areas, he tends to be given most of the credit for this discovery.”

Wilson’s paper published before Stevens’s, and as the man with the higher reputation it’s he who has been credited with the discovery. But even though their papers were similar, it was Stevens who presented a stronger — and ultimately more correct — conclusion.

Wilson still believed environmental factors played a role in determining sex. Stevens said it was purely the chromosomes. Neither view could be confirmed absolutely at the time of the discovery.

But though time proved Stevens correct, it’s Wilson who got the credit. At they very least, they should be considered co-discoverers.

It’s a classic case of the “Matilda effect,” a term named after the abolitionist Matilda Gage. The effect is the phenomenon that women’s accomplishments tend to be co-opted, outright stolen, or overshadowed by those of male peers. Stevens is far from the only woman scientist to have this happen to her: Rosalind Franklin, whose work was crucial to the discovery of DNA, got similarly sidelined later in the 20th century.

The New York Times wrote an obituary about Stevens when she died in 1912 from breast cancer. Here’s how it summed up her accomplishments: “She was one of the very few women really eminent in science, and took a foremost rank among the biologists of the day.”

An understatement indeed.

(As published on http://www.vox.com/2016/7/7/12105830/nettie-stevens-genetics-gender-sex-chromosomes)

No comments:

Post a Comment